In October 1917, [Senator Robert La Follette] delivered a blistering address in defense of free speech and dissent. “Since the declaration of war, the triumphant war press has pursued those Senators and Representatives who voted against war with malicious falsehood and recklessly libelous attacks, going to the extreme limit of charging them with treason against their country.” There have been many attacks, he went on, against him personally and demands that he be expelled from the Senate. But such attacks were not just aimed at politicians but were also being directed at ordinary citizens in an attempt to coerce them into silence and acquiescence in an unjust war. “The mandate seems to have gone forth to the sovereign people of this country that they must be silent while those things are being done by their Government which most vitally concerns their well-being, their happiness, and their lives.” This was deplorable. American citizens must not be “terrorized” in this way. He produced several affidavits of Americans being subjected to unlawful arrest merely for expressing opposition to the war. “Honest and law-abiding citizens of this country are being terrorized,” he admonished, even though they have committed no crime. Throughout the nation “private residences are being invaded, loyal citizens of undoubted integrity and probity arrested, cross-examined, and the most sacred constitutional rights guaranteed to every American citizen are being violated.” Of course, he conceded that citizens recognize that in time of war security measures are needed that might chip away at some civil liberties, but, he emphasized, “the right to control their own Government according to constitutional forms is not one of the rights that the citizens of this country are called upon to surrender in time of war” (La Follette’s emphasis). When the country is at war, he went on, it is even more necessary to preserve this right than it is in time of peace. In wartime the American citizen

“must be most watchful of the encroachment of the military upon the civil power. He must beware of those precedents in support of arbitrary action by administration officials which, excused on the pleas of necessity in war time, become the fixed rule when the necessity has passed and normal conditions have been restored.

More than all, the citizen and his representative in Congress in time of war must maintain his right of free speech. More than in times of peace it is necessary that the channels for free public discussion of governmental policies shall be open and unclogged.”

The most important right the American people enjoy is the right “to discuss in an orderly way, frankly and publicly and without fear, from the platform and through the press, every important phase of this war; its causes, and manner in which it should be conducted, and the terms upon which peace should be made.” And any attempt to stifle free speech, public discussion of the war, or even severe criticism of the administration’s policies, is “a blow at the most vital part of our Government.” 1

Many Americans applauded La Follette’s stance. Even former President Theodore Roosevelt was furious about Wilson’s attempts to suppress dissent. When Wilson’s supporters said it was wrong to criticize the president, especially in time of war, Roosevelt lashed out angrily. “To announce that there must be no criticism of the president,” he said, “or that we are to stand by the president, right or wrong, is not only unpatriotic and servile, but is morally treasonable to the American public. Nothing but the truth should be spoken about him or anyone else. But it is even more important to tell the truth, pleasant or unpleasant, about him than about anyone else.” 2

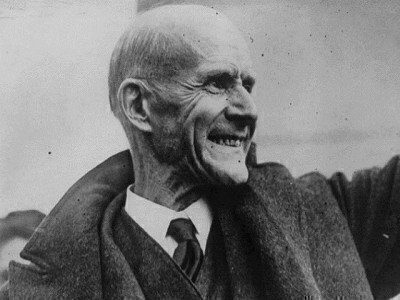

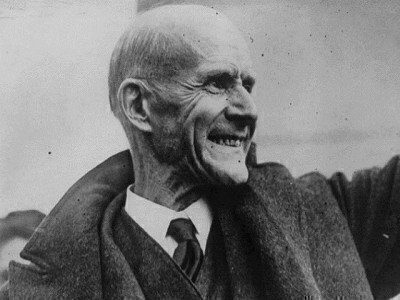

But many of those who dared to “tell the truth, pleasant or unpleasant” found themselves in trouble with the law. In June 1918 Socialist Party leader Eugene V. Debs was arrested under the provisions of the Sedition Act for a scathing antiwar speech he gave in Canton, Ohio. “Wars throughout history,” Debs reflected, “have been waged for conquest and plunder.” When Feudal lords in the Middle Ages sought to increase their domains “they declared war upon one another. But they themselves did not go to war any more than the modern feudal lords, the barons of Wall Street go to war.” It was the serfs, the peasants who fought and died in the battles back then. “The poor, ignorant serfs had been taught . . . to believe that when their masters declared war upon one another, it was their patriotic duty to fall upon one another and to cut one another’s throats for the profit and glory of the lords and barons who held them in contempt.” This has not changed. Now, just as then, it is the master class that profits from war, the working class that dies in wars. “They have always taught and trained you to believe it to be your patriotic duty to go to war and to have yourselves slaughtered at their command. But in all the history of the world you, the people, have never had a voice in declaring war, and strange as it certainly appears, no war by any nation in any age has ever been declared by the people.” 3

The Great War, Debs insisted, is an imperialist war for the benefit of American businessmen and financiers—the Wall Street gentry—who he likened to the Junkers, the autocratic Prussian ruling class that was the force behind German aggression. These “Wall Street Junkers” were lying about the war’s goals when they say it is the war to make the world safe for American democracy. The war is really about profits, nothing else. They wrap themselves up in patriotism and intimidate the people by questioning the patriotism of anyone who does not wholeheartedly support the war. “These are the gentry who are today wrapped up in the American flag,” Debs scoffed,

“who shout their claim from the housetops that they are the only patriots, and who have their magnifying glasses in hand, scanning the country for evidence of disloyalty, eager to apply the brand of treason to the men who dare to even whisper their opposition to Junker rule in the United Sates. No wonder Sam Johnson declared that “patriotism is the last refuge of the scoundrel.” He must have had this Wall Street gentry in mind, or at least their prototypes, for in every age it has been the tyrant, the oppressor and the exploiter who has wrapped himself in the cloak of patriotism, or religion, or both to deceive and overawe the people.”

These deceivers are the real traitors, Debs insisted, not those who criticize the war, not those who stand up for liberty and justice. Those are the real patriots. 4

Shortly after Debs delivered this speech, he was arrested, tried, and sentenced to ten years in prison. Along with his prison term he was stripped of his American citizenship. “I have been accused of obstructing the war,” Debs said when he was permitted to speak to the jury before sentencing. “I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war. I would oppose war if I stood alone.” 5 But then he also confessed that he believed in the Constitution. “Isn’t it strange that we Socialists stand almost alone today in upholding and defending the Constitution of the United States? The revolutionary fathers who had been oppressed under king rule understood that free speech and the right of free assemblage by the people were fundamental principles in democratic government. . . . I believe in the right of free speech, in war as well as peace.” 6

Ralph Young is a Professor of History at Temple University, where he runs a weekly discussion forum, the “Dissent in America Teach-ins,” that deal with the historical background of controversial contemporary issues. He is also the author of Dissent in America: The Voices That Shaped a Nation, a compilation of primary documents of 400 years of American dissenters. http://dynamicsofdissent.tumblr.com/

Footnotes

1) Robert La Follette, speech to the Senate, Congressional Record, 65 th Congress, first session, Volume 55, 7878-7888 (October 6, 1917).

2) Theodore Roosevelt, editorial in the Kansas City Star, May 7, 1918.

3) Eugene Debs, “The Canton, Ohio Speech, Antiwar Speech,” June 16, 1918, available online at http://www.Marxist.org

5) Quoted in Ernest Freeburg, Democracy’s Prisoner: Eugene Debs, The Great War, and The Right To Dissent (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 99.

6) Scott Nearing, The Debs Decision, 2nd edition. (New York: Rand School Of Social Science, 1919), 18, 24, 25. Also see Debs, “address to the jury (1918),” in Protest Nation: Words That Inspired A Century Of American Radicalism, ed. Timothy Patrick McCarthy and John Campbell McMillan (New York: new press, 2010), 30; and Freeburg, Democracies Prisoner, 100.